How to Cure Lower Back Pain with Proper Movement Patterns

Written by Christopher Ioannou, BSc (Hons) Sports & Exercise Science

Reading Time: 13 minutes

The video version of this post:

Treating Back Pain Traditionally vs Holistically

Now, many of you have probably tried at least one or even all of the traditional methods of treating the pain. I’m talking about physiotherapy, chiropractic manipulation, massage, medication… and the list goes on. However, despite all the efforts, the pain just keeps coming back.

First off, I must tell you that it’s not your fault. These methods are not meant to fix a back problem; they are rather designed to treat the symptoms of a back injury.

What we are interested in is finding the root cause of the pain.

Therefore, the key questions we need to ask ourselves are:

Figure 1 - Identify the Cause, then work on Prevention

“What got me into this position in the first place? And how can I prevent it from ever happening again?”

Getting these questions answered must start with the right education.

The more we know about what causes back pain, the better decisions we can make on a daily basis to prevent it from happening again and again.

The fact is, there are many causes of back pain and a plethora of solutions. Dr. Stuart McGill, who is one of the leading experts in the field of spine biomechanics describes these causes as ‘injury mechanisms’ and has written many books on how to identify and eliminate these problems.

My extensive review of McGill’s work, among others, forms the foundational knowledge behind this post.

I will be discussing a basic concept which will help you understand the fundamental relationship that the spine has with the rest of the body.

Through explaining this set of ideas, we’ll then be able to better answer the two important questions posed above.

Anyways, let’s get learning.

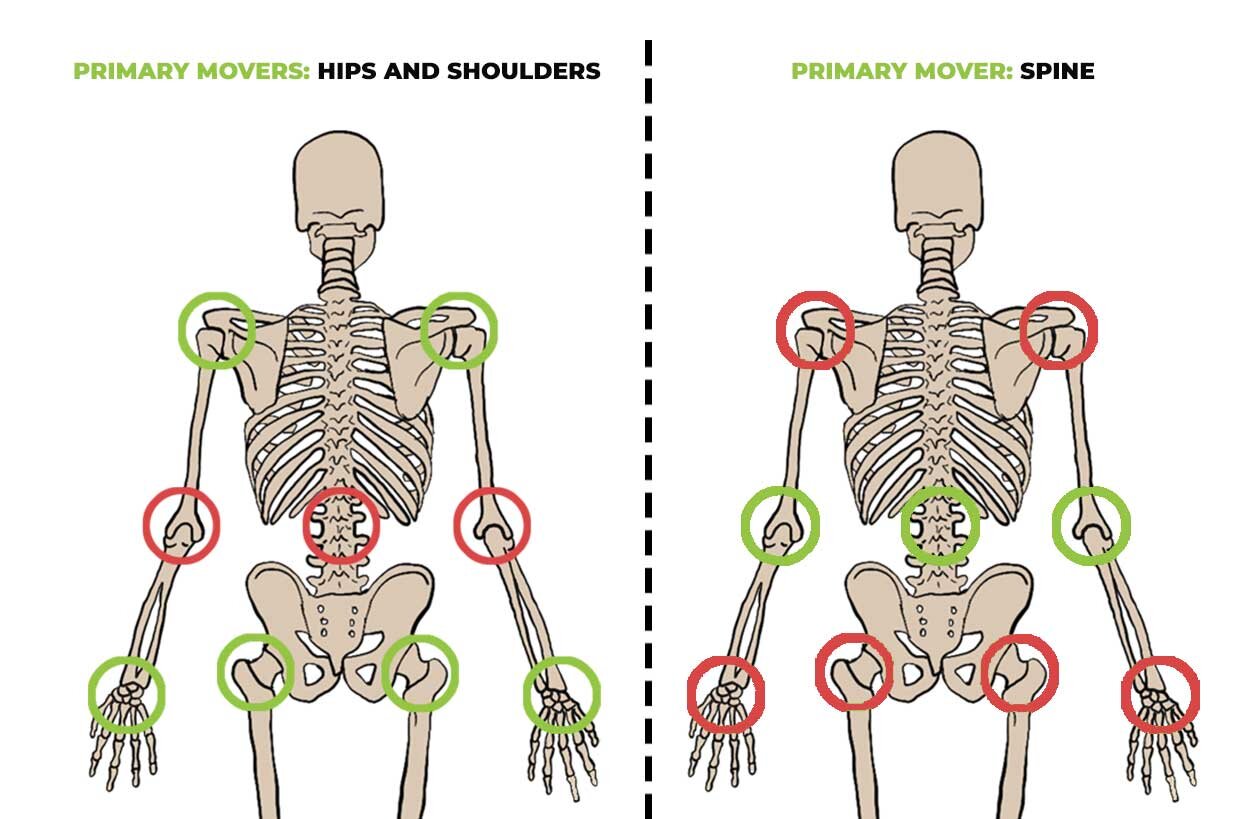

The Spine vs Hips & Shoulders as the Primary Movers of the Body

Okay, so we will begin with a short explanation on how the spine moves in relation to all the other joints in the body.

Figure 2 - Spine Flexion and Extension

The spine can flex to pick things up and extend to lift them.

Figure 3 - Spine Rotation

The same structure can rotate to swing a club and throw a ball.

But wait, let’s zoom out.

Figure 4 - Moving Through the Hips

The hips can also flex and extend to pick things up, while the shoulders and hips together, can rotate to swing a club and throw a ball, all this being done with a neutral and stable spine.

Mmm, So which scenario is better?

Well in the first example, the spine is used as the primary mover and dominates the system.

In the second example, the hips and shoulders are the primary movers, while the spine remains stable and takes the energy they create and transfers it into the objects being lifted, swung or thrown.

It is thus safe to say that the second scenario is more efficient, because it better utilises the entire body for a specific task, as opposed to overloading one system like the spine.

This is a great example of functional anatomy, which cannot be properly understood by isolating a specific area, like the spine, while disregarding the rest of the joints.

After all, the body is a system that is joined together by synergistic components.

Continuing with this train of thought, let’s consider the following:

Prioritising Spine Stability over Flexibility in the Joint-by-Joint approach

Should we stretch our back and improve flexibility of the spine in order to prevent back pain?

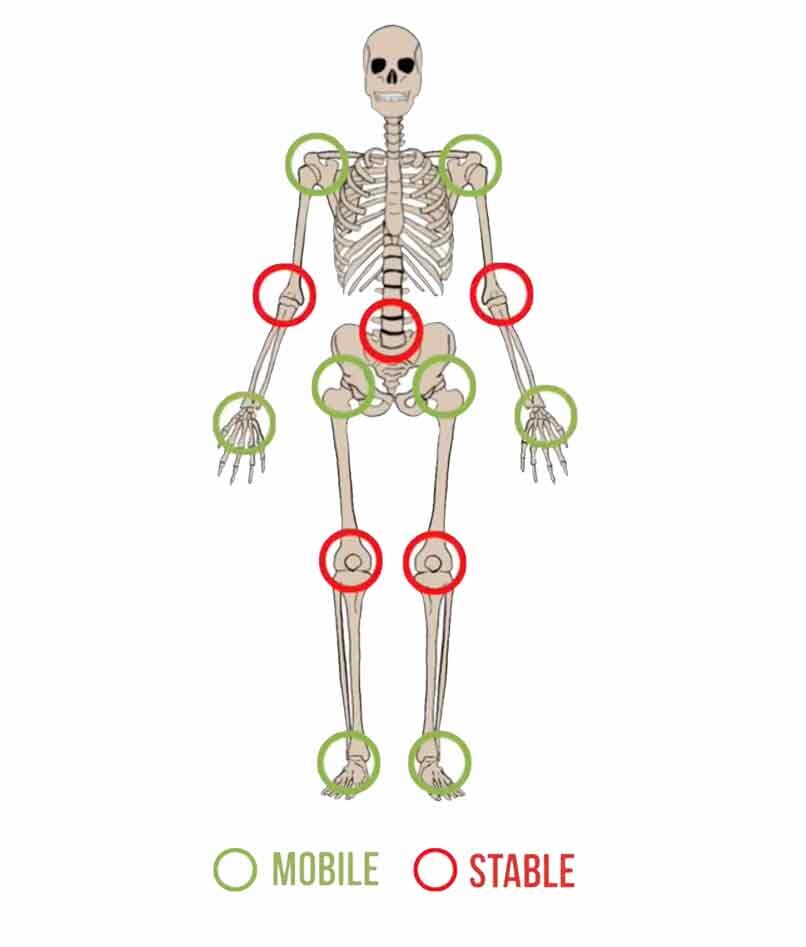

Well, first we need to understand that we have two types of joints: The hyper-mobile ones, situated at the ankles, hips, shoulders and wrists. We then have the less mobile, more stable joints of the knees, spine and elbows.

Figure 5 - Joint-by-Joint System

In context, all of these joints follow a pattern. It goes like this: Mobile, stable, mobile, stable, mobile, stable, mobile. This pattern is known as the ‘joint-by-joint sequence.’

Figure 6 - Weightlifting Protective Equipment

It is for this reason that knee straps, weightlifting belts and elbow sleeves are commonly used to increase support of these stable joints, to preserve this sequence, during lifting.

So, based on this knowledge, of functional anatomy, it makes little sense to increase the spine’s flexibility, the primary role of which is to remain stable in this beautifully sequenced system [4][5].

Famous strength coach; Michael Boyle and well known Physical Therapist; Gray Cook discovered this joint-by-joint pattern while having a thought provoking discussion with each other about human anatomy.

This pattern, as explained above, is one which utilises the best traits of each joint and attempts to explain them in context of the whole human movement system. ⠀

Now, granted, this approach is not perfect and there are still many nuances which present themselves in this anatomical system.

Nevertheless, the ‘joint-by-joint’ approach serves as a good foundation to our understanding of functional anatomy.

Understanding the Spine in Context of a Bigger Sequenced System

Figure 7 - Human Spine

So, as was briefly explained above, without a broad perspective on human movement, one could zoom in on the lower back and notice that it can flex, extend and rotate.

One could then deduce that making the spine better at all these movements, through stretching and improving flexibility, is the best way to optimise performance and decrease the risk of injury.

This is, however, very narrow-minded reasoning.

A far better approach is to take into account the other joints upstream and downstream of the focal point, that is, the spine. ⠀

Let’s now dive a little deeper into the science to understand exactly how we can preserve the spine’s primary role of stability within the joint-by-joint sequence.

1. Hips and Shoulder Joints vs Spinal Vertebrae as the Primary Movers

Figure 8 - Hip and Shoulder Ball/Socket Joints VS Spine Column

Firstly, notice that the hips and shoulders are ball-and-socket joints that can move in many different directions and have a wider range of motion than the spine. They are thus better equipped to flex, extend and rotate than the spine is capable of doing.

Secondly, the surrounding musculature at the hip and shoulder joints are also more powerful at producing force than the spine.

2. Glutes vs Lumbar Erectors

Figure 9 - Glutes VS Lower Back Muscles

Take, for example, the gluteus muscles, which drive the hips. These muscles are often called the powerhouse of our body, because they are the biggest muscles we have and they can generate tonnes of power [6].

Now compare that powerhouse to the tiny muscles we have in our lower back... There is no comparison! So, why would we want to use smaller, less powerful muscles to generate force and move the body when we can use bigger ones?

3. Spine Stability for Optimal Force Transfer

Okay, so you have highly mobile joints above and below the spine, which also have surrounding muscles that can generate loads of force at those hinges.

Now, this force has got to be transmitted through the body into the environment and the objects with which we are interacting. So, it’s pretty obvious, then, that the spinal column that joins these two power houses needs to transmit – rather than generate – all the force.

Figure 10 - Energy Transfer through the Spine and into the Barbell on Back Squat

Look at the barbell squat as a prime example. The legs and hips generate the force, which gets transmitted through the spine and into the bar, so that one can overcome gravity and lift the barbell.

The more stable the spine is, the more efficiently the force can be transmitted into the bar. The same goes for any other movement.

So, what’s better, having a robust steel rod of a spine to do this job or a flexible spine like a piece of spaghetti? I think the answer is pretty obvious.

The Spine in Context of the Joint-by-Joint System

Okay. I assume we have all reached the logical conclusion that the spine is probably best kept stable and in a neutral shape, while allowing the hips and shoulders to do the moving and produce the force during athletic activities. We can then further deduce that compromising this natural position by moving or stretching it might lead to spinal injury.

This approach will serve us well when trying to make sense of the contradictory evidence and opinions in the health and wellness realm regarding lower back pain.

Okay, so now that we understand the concept of the joint-by-joint system and how we should view the spine in the context of the entire body, let’s look at some practical examples of how our spine can be prevented from doing its job as a stable structure.

How Tight Shoulders Cause Spine Instability

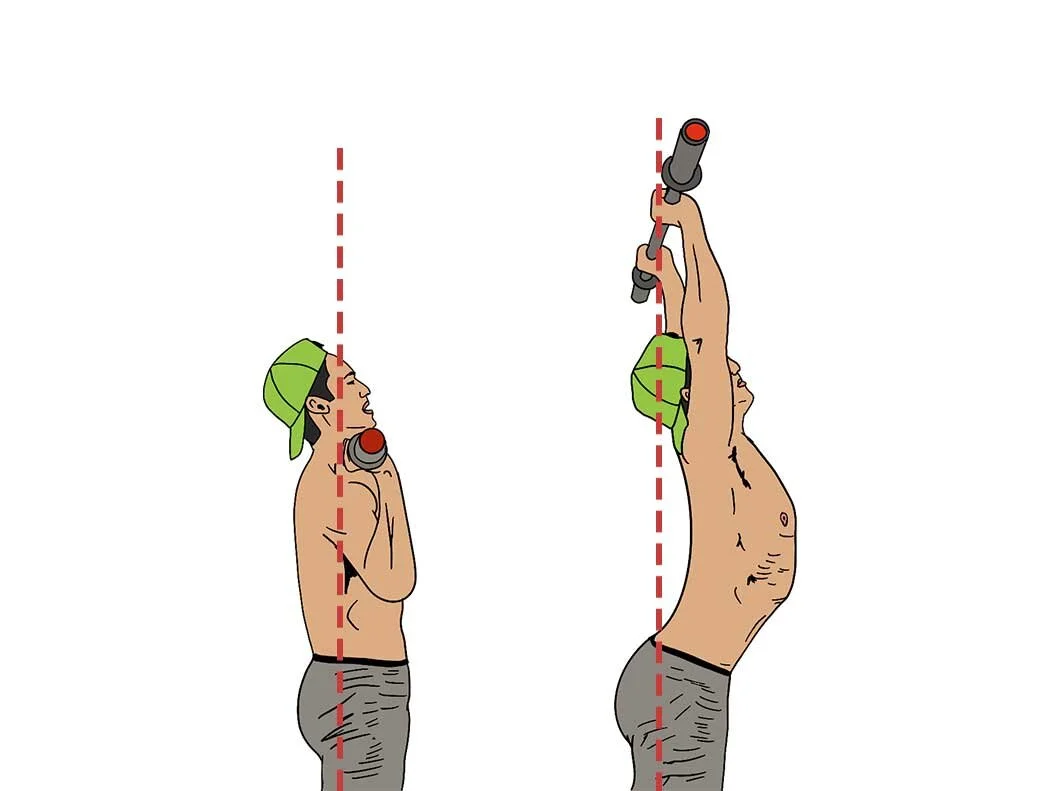

Figure 12 - Proper Overhead Press VS Tight Shoulders Overhead Press

Based on this joint-by-joint approach, let’s say, for example, that your shoulder complex is super stiff. Now you try press a barbell overhead. What is supposed to happen is that the shoulders flex up above your head, while the upper back extends to allow the weight to remain perfectly balanced over your centre of mass.

However, tight shoulders and a stiff upper back won’t allow proper motion overhead, so the weight will always remain in front of the body.

So, what do you do to compensate for this shoulder and thoracic spine restriction? After all, you need to somehow get the weight back over your centre of mass and into a balanced position in order to meet your objective of completing the lift, right?

Figure 13 - Sacrificing Spine Position in Order To Get The Barbell Overhead

Well, the only logical way to compensate for the tight shoulders and upper back is to forgo lumbar spine stability and hyper-extend the lower back [7].

The ribcage has to also flare out and the abdominals must lengthen.

So, you essentially switch off many of those core stabilising muscles, which you have worked so hard to train.

It’s like having the best running shoes, which help you finish a mile in under 5 minutes. But then you use them to try to run on slippery ice and, no matter how fast you move your legs, they just have no grip with the ground to move you forward.

Let’s give one more example:

How Tight Hips Cause Spine Instability

You go to pick something up... let’s say it’s a barbell.

So, you start flexing nicely through the big ball and socket joints of the hips, but then they hit end-range, because your hips are so tight that, at a certain point, they just won’t hinge any further.

However, that doesn’t stop you from lifting, because, after all, that’s why you went to the gym in the first place.

Figure 15 - Hinging at the Hips VS at the Back

So, the only logical way to reach the bar is to destabilise the spine, and grab the bar with a rounded back.

Because the hips are tight, the spine is called on to change its primary role in the movement and do the job of the hips instead.

These common occurrences were seen in a study done in Korea, in which the researchers found that those of their participants who were identified as having unstable spines had significantly tighter hips than the group with stable spines [8].

The Causes of Lower Back Pain (in a Nutshell)

The bottom line is that tight and dysfunctional joints above and below the spine will promote inefficient movement strategies of the spine. If the function of the restrictions in these associated joints are not fixed, it will dramatically increase the risk of injury to the spine in the long run.

So, in the scenarios provided above, even if you know that the spine must remain straight and stable, but the primary movers, that is, the hips and shoulders, aren’t mobile enough, then the spine has to lose stability to complete the movement and make up for the dysfunction upstream or downstream.

Figure 16 - Spine and Primary Movers Swapping Roles

It’s like the spine and the primary movers are swapping roles in the joint-by-joint sequence.

So, the short answer to the first question given in this article – What got me into this position in the first place? – is that your back pain could be caused by the fact that your mobile joints aren’t as mobile as they should be, causing you to sacrifice spine stability and use your back muscles incorrectly, as a compensation mechanism.

How to Prevent Lower Back Pain

Now for the second question – How can I prevent it from ever happening again?”

Well, as a sort of checklist, you must always check the following when evaluating a joint-by-joint sequence and how your body measures up to it:

First identify the primary role of the joint in question, that is, whether it is responsible for stability or mobility.

Then, make sure that the upstream and downstream joints are functioning properly to preserve the joint-by-joint sequence.

Finally, perform stability exercises or mobility drills to the relevant areas to enhance either stability or mobility, based on its identification from the first 2 steps.

Great, so let’s say you have spent time improving the flexibility of dysfunctional joints upstream and downstream of the spine. The shoulders are nice and mobile and the hips are restored to their full range of motion. You have also spent time doing core stability exercises...

Is that it? Are you all good now?

Building Better Movement Patterns

Well, not so fast. You see, when you had all these bodily restrictions and dysfunctions, you moved in a certain way. For example, maybe you habitually rounded your back when you bent down to pick up something from the ground due to tight hips. This became your default movement pattern. So, the chances are that, even when the hips become more mobile, that engrained movement pattern of rounding the back will still stick.

We could say that movement patterns are like our installed software and the body is the hardware. When we upgrade the hardware by mobilising the right joints and strengthening or stabilising others, we then need to update the software so that it can properly utilise the hardware.

Figure 18 - Poor Movement Patterns = Running Windows 98 on the Latest Gaming PC

So, not practicing good techniques and movement strategies in combination with all the mobility work and exercising is like having the latest and greatest gaming PC but only having Windows 98 installed on it.

Summary

So let’s now quickly summarise what we have covered in this video.

1. There is no quick fix when it comes to lower back pain. The only way to rid yourself of back pain, in the long term, is to have the right knowledge to identify the root cause of the problem.

2. Even though the lower back can function in many ways, its true purposes is to remain stable in a neutral position so that power generated by the extremities can be effectively transmitted and transferred through the back and into the environment and the objects we are interacting with.

3. In order for the lower spine to successfully do its job, the upstream and downstream joints must be functioning properly so that the joint-by-joint sequence can remain true to its intended pattern.

4. Once the different segments of the body (or ‘hardware’) are functioning properly, the correct movement patterns (‘the software’) must be learnt in order to utilise the body correctly and preserve the spine.

That’s it from us today! We hope you enjoyed our blog post.

For more Health Science Made Simple, subscribe to our YouTube Channel and join our Newsletter.